It is no secret that a homosexual cabal has infiltrated the Catholic Church in America. Indeed, this cabal often targets good priests and seminarians who seek to blow the whistle on the crisis in the Church.

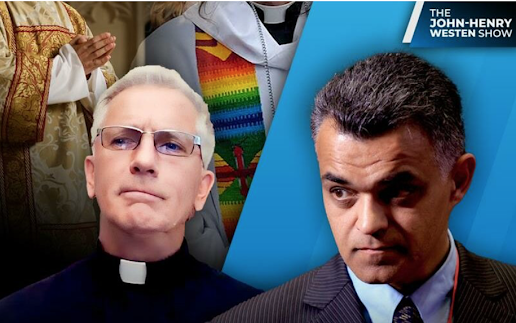

My guest today is Father John “Jack” Harrington, a priest from the Diocese of Fall River in Massachusetts. He tells me the story of how he became a “canceled priest” for attempting to speak out against what he thinks is a homosexual cabal in the Church.

Harrington applied to enter St. John’s Seminary in Brighton, Massachusetts, in the late 1980s after a successful career in education, serving at one time as a high school teacher and principal. While attending St. John’s, he received a “sexual overture” from the seminary’s academic dean, Father Jack Farrell, something that Harrington maintains “led me to… being a canceled priest.”

After helping a Canadian priest write a letter to Cardinal Bernard Law, then Archbishop of Boston, about the incident, Law sent one of his auxiliary bishops, Robert Banks, to talk to Harrington about the allegation. According to Harrington, Banks “indirectly reprimanded” him over the letter for not “keeping [the situation] in the diocese.”

Eventually, Harrington took a year off of seminary in 1991, in part because of Farrell’s presence. In 2002, Harrington attempted to reapply for the seminary, though was rejected after a psychological examination.

Likening what happened to him at St. John’s Seminary to what Michael Rose writes about in a book called Goodbye Good Men about the corruption of Catholic seminaries and the “re-envisioning of the Church” and the priesthood, including the acceptance of homosexuality, Harrington maintains the reason why his application was rejected was because “it was clear to [the seminary] I didn’t share that vision, and they didn’t want me back,” and that the “rogue psychologist” that did the examination “misrepresented” him in a series of interviews.

Harrington then applied for seminary in the Diocese of Fall River, run by then Bishop Sean O’Malley, now Cardinal and Archbishop of Boston, who sent Harrington to Mount Saint Mary’s Seminary in Maryland. Harrington was ordained to the priesthood in 2004.

When serving as an assistant priest in the Diocese of Fall River, however, he was accused of stalking a boy in his parish’s confirmation class. The allegation, however, originated with a priest that was a close friend of Farrell, Father William Costello, who alleged that the boy’s mother accused Harrington. Making the matter more complicated was that the pastor whom Harrington served under, Msgr. John Perry, was not just the vicar general of the Diocese of Fall River but a personal friend of Costello. According to Harrington, the accusation was a “total fabrication.”

Harrington filed a civil and canonical lawsuit against Perry and Costello, with affidavits from the mother and sister of the boy whom he allegedly stalked maintaining his innocence. Perry later told Harrington that the accusations came from Costello. Harrington is unsure why Perry was involved.

Eventually, the bishop of Fall River, George Coleman, ordered Harrington to drop his suits. When Harrington said that he would, Coleman told him to go to a psychologist because he spoke to the parishioners about the case. In the meantime, Harrington wanted Coleman to acknowledge that Costello fabricated an accusation against him, something that he was unwilling to do.

Coleman sent Harrington to a “priests’ hostel” as a result, and Harrington filed a canonical suit against him. As of now, Harrington cannot wear clericals in public, does not have priestly faculties, and has been “evicted” from properties belonging to the Diocese of Fall River. When he failed to find success in the canonical courts regarding his case, Harrington filed a civil suit.

“I persisted in trying to get to the truth of this thing,” Harrington tells me. “As it turned out… what I learned from going through the civil process, is that the Justices helped me a great deal.”

“The [Superior Court Justice] said it is undisputed that Harrington never stalked the … boy,” Harrington recalls, adding that the Justice maintained “the statements when made by both defendants [Perry and Costello] were harmful and scandalous and devastating to the plaintiff’s… reputation.” Unfortunately, the Justice also told Harrington that he could not proceed with his suit because the statute of limitations had passed.

Eventually the Supreme Court of Massachusetts requested to hear Harrington’s case, something he and his lawyer had not requested. When the case was heard by the court, Justice Ralph Gants maintained that Harrington was framed. At that point, Harrington realized that the boy he was supposed to have stalked only accused him of stalking so he could not continue in his confirmation class.

After the case, Harrington attempted to reenter priestly ministry on multiple occasions. The last time there was an attempt to resuscitate his faculties, three diocesan officials were involved: a woman with a legal background, the vicar general of the diocese, and the diocese’s vicar for clergy. The woman told Harrington that they were going to speak to Coleman’s successor, Bishop Edgar Moreira da Cunha, about the matter, and that Harrington had not received “justice.” However, da Cunha canceled the meeting.

“All we were asking for, and they all agreed, was an acknowledgment that Costello had fabricated this allegation against me,” Harrington tells me. “He wouldn’t do that. Neither would Coleman.” According to Harrington, it is likely an issue of the bishops attempting to protect homosexual priests, recounting how Law moved priests accused of sexual abuse around the Archdiocese of Boston.

Harrington also describes the situation priests find themselves in, relating that “if they speak up, if they witnessed something, and particularly, if it’s the homo lobby or homosexual current… they run the risk of being… subjected to reprisals by priests in the diocese,” maintaining that such is what happened to him.

What Harrington wants now is an investigation to see who used the boy to fabricate the accusation leveled against him. “By the grace of God, I just did everything by the book,” Harrington emphasizes about how he handled his case.

“There should be an investigation into this,” he continues. “Either it should be [by the] state, or even a federal [investigation], because some very powerful forces used [this boy] to do this.”

“This should be addressed, because… the likelihood is it happened to me… it could happen to other priests,” Harrington warns.